We’ve been hearing this from a wide range of fields, from students to professors, and perhaps most alarmingly, from two of the world’s largest democracies rejecting evidence based policy to elect anti-science policy makers. The culprit is claimed to be peer review, or badly understood statistics, scientists being too wrapped up in public engagement, scientists not doing enough public engagement, the terrible way we treat our science teachers, our devaluing of degrees . . .

I don’t think it’s any of these. I think the real cause of the scientific crisis is specialism.

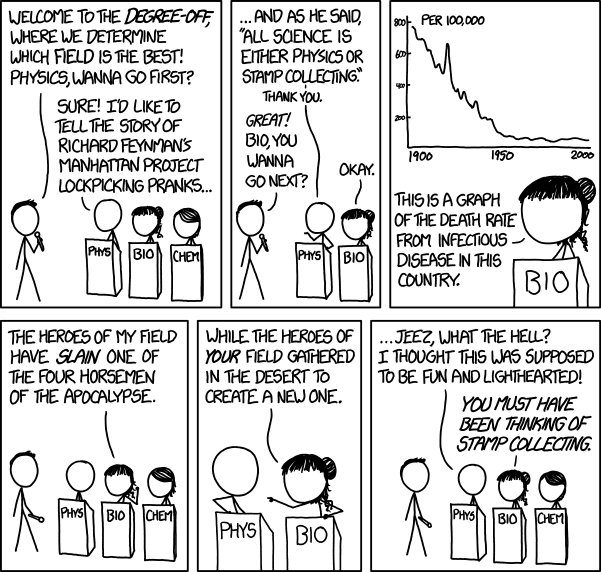

Before going any further I want to point you towards two comics in the venerated xkcd. Purity and Degree Off. As an interdisciplinary scientist who named her blog ‘Fluffy Sciences’ I open many of my lectures with these concepts. I used to open with Purity long before Degree Off was posted because it makes such an important point. The culture of science has a deeply ingrained problem with application. The more applied a scientist is, the more we look down on them. A mathematician is worth a dozen engineers because at the end of the day, the mathematician can be taught to do anything the engineer can. As the mathematicians say, everything comes down to numbers eventually.

I am not immune to this belief. I’ve spent a lot of my scientific career fighting my own applied nature. When I was specialising in behavioural ecology I maintained that I was interested in the broader – and more serious – sphere of ecology. When I started working in ethology I clung to that behavioural ecology badge like a shield. When I realised I was getting deep into interdisciplinary territory I started reaching for the word ‘ethology’. If I had an ology I’d be fine. Interestingly, in my interview for my current role I was asked what attracted me to educational research. My answer was that I liked working at the coal face, I liked being able to quickly see the impact of a change.

My answer was honest, and applied, and reader? I have never been happier professionally than I am in my current role.

Recently I feel as though I’m hearing the same thing, over and over. Whether it’s what I have been writing in my application to the Higher Education Academy, whether it’s listening to how the Applied Animal Behaviour and Welfare MSc has changed over the years, or whether it’s listening to Dr Chatterjee’s SEFCE plenary on functional medicine, the problem that each person describes is the same: the specialists are only interested in teaching their subject, not the skills that the world desperately needs.

Chatterjee’s talk was interesting precisely because it set off many of my little professional bugbears. Chatterjee preaches Functional Medicine, a holistic approach to a medical problem that advocates multiple small harmless changes as a first line of treatment. In theory I love the sound of it, its very similar to the approaches I advocate for welfare assessment. But Chatterjee spoke of several case studies, he couldn’t evidence sustained behavioural change for his patients, and I was desperate to ask how such a change could be implemented in a health system which needs measurable metrics both for the assessment of new medics and the quality monitoring of existing medics. These are all serious questions for advocates of functional medicine.

During the talk I tweeted my thoughts, as I often do, and I tweeted that my quantitative heart and qualitative brain were at war when thinking about functional medicine. My heart, which truly loves the comfort of describing things mathematically, rejected functional medicine’s case-by-case approach. My logical brain, which sees the value of qualitative science, understood that the real goal was not making numbers perform on a chart, but changing the intangible and immeasurable experience of the patient.

We specialise early in life. Maths is separate from English in school. You can be better at one subject than the other. I think back to my early years at university. In first year I had three courses, biology, chemistry and archaeology. Learn the facts about biology, this fish does that, this dinosaur likely moved like this. Learn the facts about chemistry, hydrocarbons are stable, lab safety is important. Learn the facts about archaeology, these people lived then, this is the evidence they leave behind. Facts that can be regurgitated in multiple choice questions (a very efficient and useful method of assessing knowledge). Then in second year, 8 separate biology courses. In third year, four separate biology courses, in fourth year another four separate courses. All these courses that are set up independently, assessed independently, and brought together at the end with a dissertation project.

This approach is a relic of university history where expert lecturers stood up to regurgitate everything they knew about their subject. We know that this is not the best way to teach (1, 2, 3) , and indeed even that it prevents students from making connections between subjects. Yet we persist in creating these divisions. Why?

In some respects it comes back to the need to measure success. It is always easier to measure something when you break it down into smaller chunks, and students need to be measured and to be told how well they’re doing. No student wants to study for four years and then have everything assessed at the end (well as a student that would have suited me perfectly but I don’t think I was normal). So there must be some break down of both the information and skills. The question to me is: what’s the most important thing you want every student to be able to do?

In the first year of your science degree what do you need to know? Do you need to be able to say that parrot fish are able to change sexes in single sex environments? Is it important for you to name every type of bridge structure? These may be reasonably interesting facts, but what is the application? In the last five years I have never been in a situation where that sort of knowledge wasn’t accessible via the small device in my pocket. We have out-brains now that deal with fact retention. Fact retention is the least important part of my role as a scientist.

Not only is fact retention not important for me, as an actual academic who works in research, but most of the students I teach are not going into the hallowed halls of academia. The zoologists are becoming bankers, the engineers becoming salespeople . . . regardless of what you think of it, the undergraduate science degree does not mean you will become a scientist. For those people, what’s the most important thing I could teach them? What’s the most useful thing for them to learn?

It is not the parrot fish.

Imagine a first year science degree where the first year looks like this:

Introduction to Science

By the end of this year you will be able to:

- Identify an appropriate sample frame for a range of populations

- Distinguish between interview and focus-group data

- Discriminate between positive, negative and historical controls

- Describe a manipulative study

- Describe an observation study

Those learning outcomes are all assessable via variants of multiple choice questions, but also easy to evidence in class, providing excellent opportunities for both formative and summative feedback. This meets our need to measure and give feedback for our students. I would be delighted to even work with an MSc student who could do all of these, but they are still basic skills that any psychologist, chemist, physicist or biologist should really be able to do. Not only that but the banker and the salesperson, the people with the degrees who have no intention of ever doing research. These are skills that the world needs.

You could use examples from many different fields while teaching this subject. You could show how a focus-group responds to a new bread recipe, bring in some accessory knowledge from everything from agriculture to chemistry (Learning Outcome 2). You could look at the testing of a bridge’s strength and compare that with observation of the bridge in use (Learning Outcomes 4 & 5). Even those students who do want to become scientists are interested in the how of the world, and all of these examples are interesting and worthwhile learning a little bit about.

Specialist knowledge is important, but specialists are by definition an expert in one thing. We need more people with more general knowledge. Science needs to get over its specialism fetish if it hopes to help the world move forward. Science needs to get over its specialism fetish if it hopes to help itself.

Being a physicist is not better than being a stamp collector. We shouldn’t be teaching students otherwise.