This week on Badger Fortnight we turn our attention to the rogue of the tale, the humble badger.

Did you ever read the Redwall books as a child? If the story of Bovine TB was told Redwall style, I imagine the badger would be a travelling bard, handy with a bow, flirting with the bovine ladies at the bar, upsetting the status quo and just generally causing a fuss.

Badgers biggest problem in this story is that they are a host for Bovine TB. When they catch TB and it becomes an active infection the disease develops and they become weak and emaciated but rarely actually die from the disease. They can transmit this infection back to cattle out in the fields, again through aerosol droplets.

Badgers are group living animals which are highly territorial. They live underground in setts which are protected by law in the UK. For this reason, Defra’s randomised culling trials needed special permission. You cannot simply go and shoot badgers in the UK.

The culling trial was supposed to be the humane solution to the problem of the spread of bovine TB. As you may have seen in some other posts of mine, I have no welfare problems with humane culling (although I may not like it from an ethical standpoint).

In this post I’m going to briefly go over the final Defra reports on the culling trial and discuss why I would consider it to be an abject failure.

Humaneness of the Badger Cull

The Humaneness Monitoring protocol for the cull (Version 0.4) states that:

“Killing techniques that are instantaneous without imposing any stress on the animal are universally accepted as being the ideal and having a low welfare cost. Welfare costs are assessed in two dimensions: duration and intensity of suffering.”

I’m fairly content with this definition. If the process doesn’t stress the animal and the death is fast, I consider that to be a ‘good’ death. The protocol itself states how they recorded the whether or not the cull was humane. They investigated:

- Time from being shot to death

- How many badgers escaped after being shot at?

- What do badgers do after being shot at?

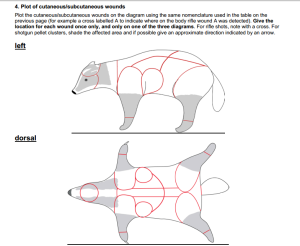

- Where on the badger are the wounds located?

- How injured are the shot badgers?

- Is there a relationship between time till death and type of injury?

- Is there a difference in the wound type between shootings observed by researchers and unobserved shootings?

This protocol also features the cutest little wound plot you ever did see.

These are the objectives the independent panel used to decide whether or not the badger cull was considered humane. But of course the cull had another objective too.

Population Control

The cull’s purpose was of course to control the badger population in the region. The Animal Health and Veterinary Laboratories Agency 2014 Report into the efficacy of the cull (Version 1) describes how the AHVLA judged the success of the cull on a population control level.

Their aim, stated at the very start, was to reduce the badger population in the Gloucestershire area and Somerset area by at least 70%. Pretty early in this report you’ll notice the words ‘cage trapping’ being used. And if you’ll scroll up just a few paragraphs you’ll notice the humaneness protocol mentioned nothing about cage trapping.

Yes, the cull, in the end, did allow for cage trapping followed by shooting. Does being confined in a small area, unfamiliar to you, for up to a day, before a human approaches and shoots you sound like a stress free death? There’s a reason ‘like an animal in a trap’ is a saying.

Moving swiftly on . . . the AHVLA sampled the number of badgers in the area using hair traps – by placing little pieces of barbed wire near setts and badger runs they collected badger hair and DNA sampled that hair to build up a profile of how many badgers were in the area. They then compared the DNA of culled badgers to their profile.

They also investigated sett disturbance by monitoring the setts and placing, in a slightly Nancy Drew esque fashion, sticks outside the setts and noting which ones were disturbed. This method was not very reliable and they stopped using it because it was estimating that the cull had taken out over 100% of the badgers in the area, even though the observers were clearly seeing badger activity.

So they stuck with DNA sampling.

Now as you may have heard, it’s important for the cull to take out at least 70% of the badgers or the disturbance in the population will simply lead to badgers redistributing within the air and increased disease transmission. The cull had to take out a large proportion of the badgers to be successful.

Now read on . . .

Cull Success – Numbers

The AHVLA report estimates that in the Gloucestershire area, the highest estimate of the number of badgers culled was 65.3%. And it could have been as low as 28%. In Somerset they removed a maximum of 50.9% of the population and as few as 37% of the population.

All of those numbers are less than the target of 70%, even the maximum estimates.

In Gloucestershire, more setts were active after the culling than before (suggesting that the cull had resulted in increased badger movement, increasing the perceived disease transmission risk). Although this didn’t happen in Somerset.

The AHVLA report concludes with the following verdict:

“From the results presented above we conclude that industry-lead controlled shooting of badgers during the entire culling period (including the initial six week period and the extensions) did not remove at least 70% of the population inside either pilot area. In both areas significantly fewer than 70% were removed by controlled shooting. The combined approach of controlled shooting and cage trapping also did not remove at least 70% of the population inside either pilot area; substantially fewer than 70% were removed in both areas. Populations of badgers were highly likely to persist within both pilot areas following culling.”

Verdict: Fail.

Cull Success – Welfare

The Humaneness Report (2014) found that only 36.1% of the carcasses they post mortemed had the first entry wound in the target location. When the contract shooters were observed this jumped to 42.9% and when they were unobserved it was 31.5%

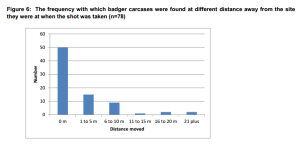

As you can see from this figure, a proportion of badgers were found some metres away from where they were shot, clearly suggesting functioning behaviours and implying suffering and pain after being shot.

The Independent Panel Report’s Conclusion

Professor Munro’s Independent Panel Report (2014) takes both these reports into account when it delivers this damning conclusion:

“We concluded, from the data provided, that controlled shooting alone (or in combination with cage trapping) did not deliver the level of culling set by government. Shooting accuracy varied amongst Contractors and resulted in a number of badgers taking longer than 5 min to die,others being hit but not retrieved, and some possibly being missed altogether. In the context of the pilot culls, we consider that the total number of these events should be less than five per cent of the badgers at which shots were taken. We are confident that this was not achieved.”

In summary, the cull failed to eradicate enough badgers to be worthwhile and it failed to do this in a method that we would consider humane.

The report also makes this mention of the problems surrounding the humaneness of the cullings:

“Further concern about the accuracy of shooting stems from the following observations:

a. Seven badgers required at least two shots, with one Observed shooting recording six shots fired at a single badger.

b. A further seven badgers (in Category C) may have been missed completely. In one of these cases two shots were fired at two badgers, with both shots being considered misses on the basis of thermal imaging observations and subsequent analysis of thermal imaging recordings.”

So on the two criteria by which the culls were launched, they failed. They are not an option for controlling bovine tuberculosis.

So what happens now?

Tune in next week . . .

I was against this because I didn’t believe that it was ever going to be effective against the spread of bovine TB, but I have to say I hadn’t considered the number of animals who may have not died immediately from their wounds, or the caging aspect of the process. Very enlightening.